|

Title: |

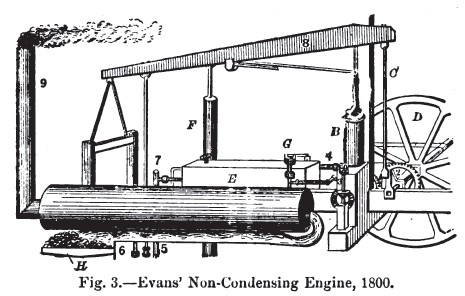

1890 Image-Mars Works, Evans Non-Condensing Steam Engine of 1800 |

|

Source: |

The Practical Steam Engineer's Guide 1890 pg 42 |

|

Insert Date: |

3/2/2011 11:34:42 AM |

This was one of the first steam engines built in the U. S.

The high-pressure or non-condensing engine was invented and first introduced by Oliver Evans, an American. This truly great man—of whose name and fame every American should be proud—was one of the most ingenious mechanics that this country has ever produced. He was born in the little village of Newport, Delaware, in 1755 or 1756, of parents in humble circumstances. He was, when a boy, apprenticed to a wheelwright, during which time he exhibited wonderful mechanical talent, and a strong desire to obtain knowledge. Subsequently meeting with a description of Newcomen's atmospheric engine, he at once noticed that the elastic force of the confined steam was not there utilized. He then designed the non-condensing engine, in which the power was derived exclusively from the tension of high-pressure steam.

In 1786 he applied to the Pennsylvania Legislature for a patent for the application of the steam engine to driving mills, but was refused it. About the year 1800 he commenced the construction of a steam carriage to be driven by a non-condensing engine; but afterwards concluded that it would be better, peculiarly, to adapt his engine, which was novel in form, and of small first cost, to driving mills. He accordingly changed his plans, and built an engine six inches diameter of cylinder, and eighteen inches stroke of piston, which he applied with perfect success in driving a plaster mill. This engine, which he called the "Columbian Engine," was of a peculiar form, as shown in Fig. 3.

The beam was supported at one end by a rocking column, and at the other it was attached directly to the piston-rod, while the crank was situated beneath the beam. The connecting-rod was attached to the extreme end of the beam. The head of the piston-rod was compelled to rise and fall in a vertical line, by the "Evans parallelogram"—a kind of parallel motion very similar to that designed by Watt. In Fig. 3, A is the boiler; B, the cylinder; C, the connecting-rod; D, tho fly-wheel; E, steam-drum; F, feed-pump; G, safety-valve; H, grate bars; 2 and 3, geared valve motion; 4, steam-pipe; 5, 6 and 7, feed-pipe; 8, the beam; 9, smoke-pipe. The flames from the furnace pass under the boiler, between brick walls, and back through the central flue to the chimney. Subsequently, Evans continued to extend the application of his engine, and perfect it in detail. He continued to build engines until he died—which sad event took place April 19, 1819—applying them with success to steamboats on the western rivers, to flour mills, saw-mills, dredging machines, elevators; in fact, wherever steam power could be applied. He has deservedly been called, "The Watt of America."

After Evans had passed away, other builders in different parts of the country went into the business, and steam-engine building became one of the great industries of the land. These engines were at first rude in design, badly proportioned, rough and inaccurate as to workmanship, and uneconomical in the consumption of fuel. Gradually, however, they assumed neater and stronger shapes, good proportions, were well made, and of good material, until today the American stationary engine is equal, if not superior, to any made in Europe or elsewhere. To prove this, the reader has but to examine the many splendid examples by our best makers, to be found in this book. In stationary engines the United States leads the world. |

|

Mars Works, Evans Non-Condensing Steam Engine of 1800

Mars Works, Evans Non-Condensing Steam Engine of 1800

|

|