|

Title: |

1891 Article-Straight Line Engine Co., Stationary Steam Engine |

|

Source: |

American Engineer, V22, 22 Aug 1891, pg. 71 |

|

Insert Date: |

6/15/2018 1:25:46 PM |

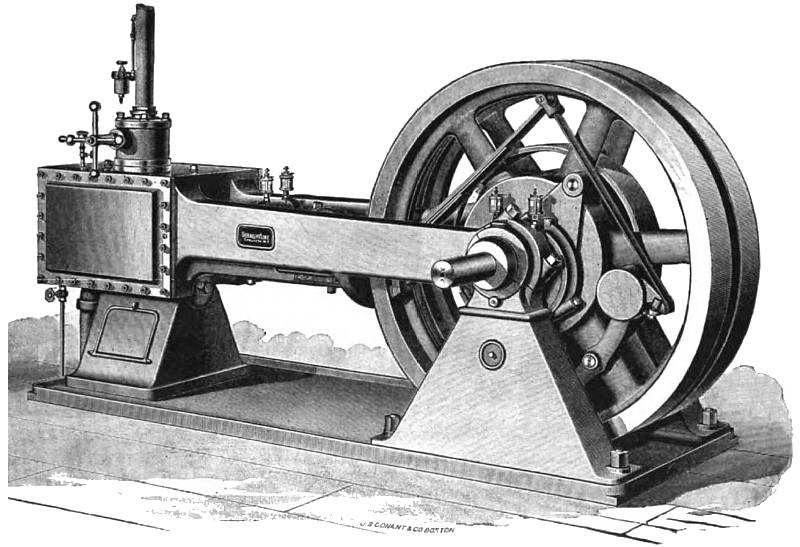

The double valve engine, shown in the accompanying electroplate and put on the market by the Straight Line Engine Co., of Syracuse, N. Y., differs from all others. Hence an explanation of its design and operation cannot fail to be specially interesting.

The plan of this engine conforms with two leading ideas, namely, that all strains go in straight lines, and that any structure having considerable length and breadth, in proportion to its depth, must be supported on three self-adjusting points of support, to be free from torsion when resting upon an unstable foundation. Absolutely solid foundations are rare and costly; but however much one may "settle," or go out of true, if the machine rests on three points, it will in no way be sprung or warped, we are positively assured. And again, if the foundation is absolutely unyielding, the three points of support are still correct, it is also well to bear in mind that when a line of strain passes directly through the center of the bar that resists it, there is no tendency to spring or bend the bar; but where the strain is resisted by a curved frame, there is always a tendency to spring.

The design of this engine is believed to be consistent in that all boundary lines are straight, ending in graceful curves; all cross sections of stationary parts rectangular, with rounded corners; and all moving arms and levers, double convex, wide and thin, with the longest axle in the direction of the greatest strain. Thus the designers have kept "the fitness of things" well in view.

The frame of this engine is cast in one piece with the cylinder and steam-chest. While this proves to be an expensive way, it has the merit of remaining true if once made so, it is said, and the form being such as to place the metal in the best possible position to resist the strains, and as the amount of metal is enormously in excess of that required, it is believed no occasion will arise when anyone having one of these engines will wish it made otherwise.

The objection has been raised that additional expense will be incurred when it becomes necessary to re-bore a cylinder; but provisions are made for re-boring, by which the work can be done more cheaply than in ordinary engines where the cylinders are removed and mounted on a lathe—it is maintained. And no wear can take place at the main journals; provision is made for facing the valve seats without Interfering with the valve adjustment; the lower guide for the cross-head is a separate casting, so no wear comes on the frame except in the bore of the cylinder.

The throttle valve of this engine, which was designed oy the late John Coffin, formerly foreman of the Straight Line Engine works, consists of a flat seat, circular in form, having a semi-circular opening through it, and a valve whose face is a counterpart of the valve seat, which may be rotated half way round by means of a semi-circular bevel gear upon its surface and a pinion. When the valve is set in such a position that the two openings coincide, there is a straight way passage for the steam, and when turned in the reverse way the valve is closed. There is no face exposed to the action of the steam when the valve is open, and when reversed, none exposed to rust. Thus, protected from both the action of steam and rust, the faces remain perfect and steam-tight for a long time after the warp by changes of temperature has been taken out. The faces being flat, they can be refitted by either scraping or grinding, more readily than any other form. The pinion, by which the valve is rotated, is cast on the stem, and that made a steamtight joint by a good fit of the stem and a ground joint at the shoulder and packed in the usual way. The threads on the bush which screws in the casing being larger than the pinion, the whole handle arrangement is removed together for shipment.

The Straight Line Engine Co. have made a new departure in piston construction. The main characteristic is that the packing rings are of what they have designated "limited expansion," that is the rings are made much too large for the cylinder, and then sprung in with considerable force, being pinned in that position and the outside turned to a perfect fit to the cylinder. The pin-holes in the rings are afterward fitted to admit of the rings being compressed while not allowed to expand. Engines smaller than ten-inch cylinder are solid with rings sprung in.

The piston rod packings are simply Babbitt metal bushings, with reamed holes slightly larger than the rods, so as to be a free sliding fit. But when specially requested the manufacturers used hemp packing instead.

The cross-head, which is of steel or malleable iron casting, is threaded on the piston rod and secured by being split and clamped by the binding bolts. The wearing surfaces of the steel castings are faced with babbitt. The cross-head pin is a hollow steel casting made fast to the connecting rod and turns in two adjustable babbitt-lined boxes in the cross-head. The object of this is to secure lightness, extra wearing surface, to prevent side swinging of the connecting rod at the fly wheel end, and to give ready means of oiling. The method of oiling is by two fixed sight feed oilers without wicking. The oil from the metal points is taken off by metal channels and conveyed to the crosshead pin from which the drip is conveyed to the lower guide, and all waste oil and water la retained in the basinhor conveyed away in an overflow pipe.

The rods are secured to the cross-head pins by clamp bolts and the crank boxes are hammered babbitt metal bored and scraped to fit. Test pins of considerable length, ground to perfect cylinders, are put in each end, and the holes tested for parallelism and truth and scraped until perfect accuracy is secured.

The steel crank pin and shafts forced into the large bosses of the two wheels form a solid structure, dividing the strain equally between the bearings, and giving an opportunity to balance the reciprocating parts properly, while furnishing a support for the governor and relieving the main bearings of a good part of the thrust of the piston. The crank pin is oiled while the engine is in motion by means of the eccentric chamber on the outside of one of the balance wheels and the holes drilled through the crank pin. The waste oil from the inner end of one of the main bearings finds its way to the crank pin also, so that the main bearing is sure to run dry before the crank pin does. The wearing surface of the crank and main journals are made exactly of the same length as the wearing surface in the babbitt-lined boxes, and as the main shafts and crank have one-quarter inch play through the boxes, grooves are turned in the shafts and cranks, so that the boxes can over-run. The ends of the shafts are reduced to the size of standard shafting, one size smaller than the bearings. The waste oil thrown from the cranks of high-speed engines has always been source of great annoyance, and one which the Straight Line Engine Co. say they have succeeded in pretty effectually overcoming by recessing the inner surface of the wheel rims so as to catch the oil and there retain it until the engine is stopped, or from which it can be wiped while the engine is in motion.

Details of the main journal boxes, and of the governor, eccentric, valve motion, and the valve, together with the exhaust, pedestals, etc., are given, with illustrations, in the company's illustrated catalogue, which may readily be obtained by those interested.

This article cannot be concluded better than by giving the "pedigree" of this engine. It was built as an experiment in 1871. A second "edition" appeared at the Cornell University in 1875, where it is still used experimentally. In 1879 the first engine was changed by the introduction of a governor of the present form, and on January 1,1880, an upright rolling mill engine was built by Sweet's Manufacturing Company, which has been in constant service since. On February 1,1880, the Straight Line Engine Company was organized, since which time they have been building the engine known by this name.

While this engine has always maintained the original characteristics, that is, a frame consisting of two straight arms running from cylinder to the main bearings with the balance wheels between, and the whole resting on three self-adjusting points of support; they have, from time to time, made such changes as experience indicated would make a more perfect machine. Many of the changes have been in the direction of simplicity, and all to make it more complete.

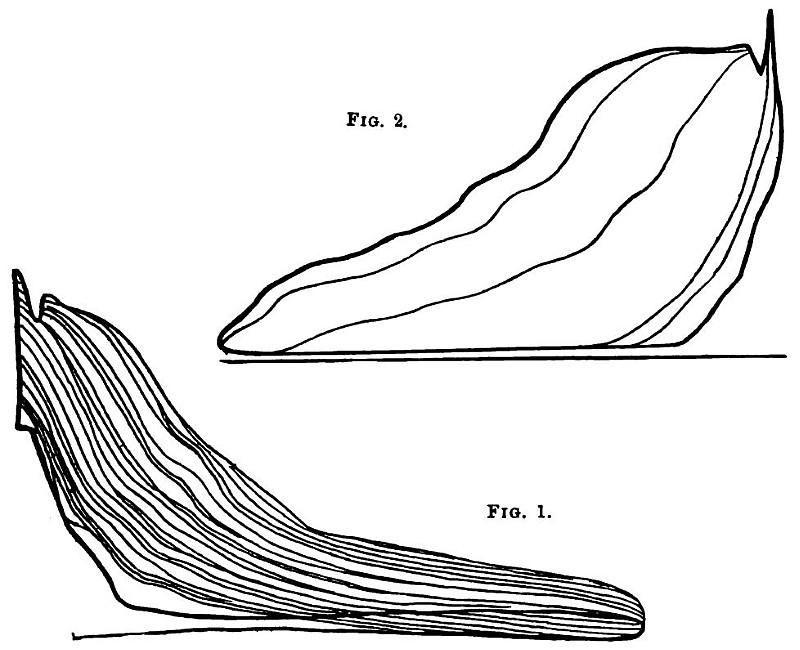

At the works of the Straight Line Engine Co., during the A. O. S. E. convention, the engineers were shown one of the company's new double valve 100 h.p. engines on the testing floor under steam with both indicators and prony brake in operation. As steam was taken from the boiler running the works, only enough for sixty horse power was available, and with this load on the prony brake, while the engine was running 220 revolutions, by a trip on the brake, the entire load was thrown off instantly. When this was done no possible variation in speed could be detected, and except for a change in sound of exhaust, which seemed to change at the same instant, no one could possibly detect that the load had been removed. During the time the load was thrown off the indicator pencils were held on the papers and in some cases only two and in others three intermediate lines appeared on the cards, showing that the governor changed its position as readily as the increase in the speed of the wheels. The change from loaded to light was a trifle less than 2%. The governor can be set to govern at any degree of sensitiveness, but 2% is considered by builders to meet practical requirements.

Another experiment shown, that interested the engineers quite as much as the foregoing, was starting the cards with the engine running light, holding on the pencils and then applying the load gradually, or as nearly so as could be done by the operator screwing up the prony brake with an open-end wrench. Time did not permit seeing the large number of interesting and novel things which this company always takes special pains to show and explain.

We received cards taken by some of the visiting engineers, while at the Straight Line Engine Works. But as neither of them showed the action with the load removed, we applied to the company for such a card. Not having an engine of the same kind on the testing floor they sent us one taken from a single valve engine, in addition to the one previously received.

Fig. 1 shows card from the double valve engine, 11x16 running 220 revolutions, with the engine running to speed light and an increasing load up to 60 h.p., applied by screwing up prony brake.

Fig. 2 shows single valve engine, 11x11 running 275 revolutions, with 70 h.p. load with prony brake thrown off instantly to 25 h.p., the brake not having slack enough to throw the load entirely off. |

|

1891 Straight Line Engine Co., Stationary Steam Engine

1891 Straight Line Engine Co., Stationary Steam Engine

1891 Straight Line Engine Co., Stationary Steam Engine (Indicator Cards)

1891 Straight Line Engine Co., Stationary Steam Engine (Indicator Cards)

|

|