|

Title: |

1871 Article-Aveling & Porter, Steam Road Roller |

|

Source: |

Manufacturer & Builder, V3, May 1871, pg. 105 |

|

Insert Date: |

2/20/2017 5:19:59 PM |

Steam Road-Rolling

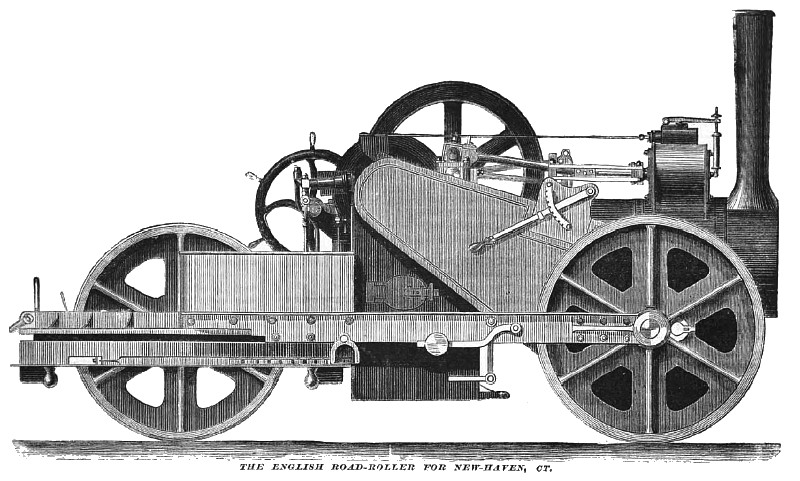

The Road Commissioners of the city of New-Haven were the first to follow in the wake of private enterprise and adopt the steam road-roller in the construction and repairs of their city streets. A deputation of the Common Council of New-Haven, consisting of the mayor and other members of the Board of Road Commissioners, visited the Brooklyn Park, and Orange, New-Jersey, in company with the authorities of Hartford and other adjacent cities, for the purpose of inspecting the action and effect of the steam-roller on broken stone pavements. The favorable impression formed by those gentlemen of the value of the roller is shown in the fact of their immediate purchase of one of these machines from Mr. W. C. Oastler, of 43 Exchange Place, New-York—Messrs. Aveling & Porter's agent in the United States. If other municipal authorities would imitate the enterprise of the " City of Elms," tax-payers would have cause for rejoicing in cheaper, better, and more durable roadways; and a material reduction in the cost of road construction and maintenance.

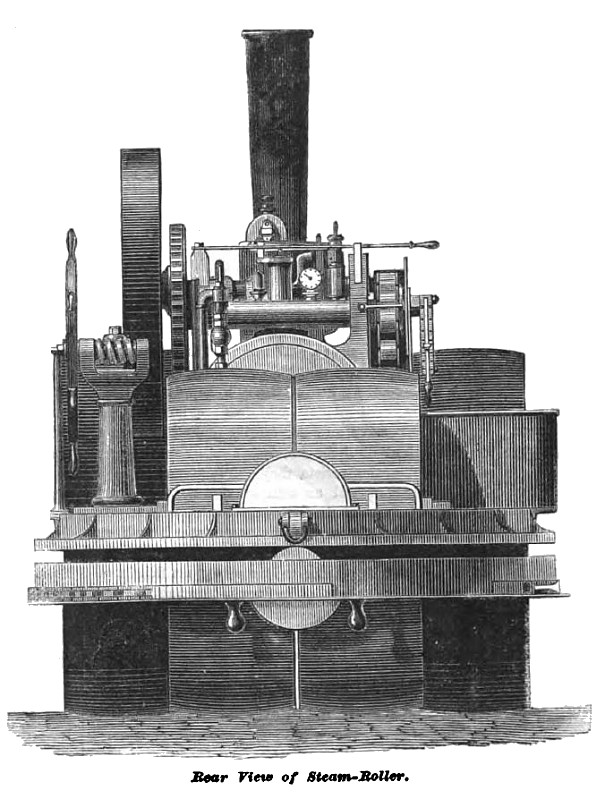

The steam road-roller is made of 15, 20, 25, and 30 tons weight; the 15 and 20 ton machines being mostly in use. For asphalt pavements, gravel roadways, and other lighter work, a steam roller weighing eight tons is used; but for the purpose of constructing and consolidating macadam roadways, this last roller is not of sufficient weight. A ten-ton roller has been found totally insufficient; and on the London Holborn viaduct, last year, a twelve-ton steam roller was tried, and abandoned by reason of the weight not being adequate for rapidly consolidating the unfinished road. Experience leads to the belief that a heavier rather than a lighter roller than fifteen tons would be more economical and efficient. The roller is an adaptation of the ordinary road locomotive to the purposes of road-rolling. The engine is carried upon four rollers of equal widths, the two in front acting as drivers, and the two hind ones fixed in a turn-table, so as to steer the engine and overlap the space left between the two driving-wheels. The single cylinder is placed on the forward part of the boiler, and is surrounded by a jacket in direct communication with it; the steam is taken into the cylinder from the dome on the top of this jacket. The pitch-chain and break-wheels are keyed fast to the driving-axle, while the driving-rollers work free upon it; so that, when turning sharp curves, either wheel can be thrown out of gear. The turn-table is arranged to admit of the driving and steering-wheels accommodating themselves to the curved surface of the road, and, as the weight is equally divided between the front and hind wheels, the compression is uniform. A powerful and simple friction-brake acting upon one of the driving-rollers, and worked by a! wheel and screw from the foot-plate, gives complete and rapid control over the machine. The roller is steered also from the foot-plate, by a chain attached to the turn-table, and worked by worm-gear. And as it can be turned around in its own length, it is calculated to roll steep hills, without injury to the fire-box.

Roads form a primary element in the advancement of a nation, being essential to the development of the material resources of the country. To cities they are of vital importance. Nothing tends to enhance value, give momentum to business, and furnish the means of comfort and pleasure, more than well-constructed roads and streets. They are the great arteries of corporate vitality.

Seventy years ago, when John Loudon Macadam, a man to whose energy and talent England and the world at large owe more good roads than to any other, was in the zenith of his popularity, he perhaps little contemplated that steam would be employed as a power in the construction and repair of Macadam roads. It is clear, however, that Macadam's definition of a road " as an artificial flooring, forming a strong, smooth, solid surface," is only fulfilled by rolling it; and then, and not until then, is it "at once capable of carrying great weight, while offering a surface over which carriages may pass without meeting any impediment." Macadam, who worked and wrote before road-rolling was practiced, gave it as his opinion that "carriages, whatever be the construction o{ their wheels, will make ruts in a new made road until it consolidates, however well the materials may be prepared, or however judiciously applied." The main difference between a rolled and an unrolled road is, that the first contains nearly three times more empty space than the latter. It is certain that a road cannot be hard and strong until these spaces are filled up. Without the rolling, this can only be done by the particles ground by the traffic off the edges of the stones, by dirt, etc.

Under such circumstances, a so-called macadamized road left to itself and the traffic to consolidate it, became a mixture of stone and rubbish, the latter always working up to the top, as the loose stones are worked down, causing an unenviable quantity of dust and dirt, and an uneven roadway, the premature destruction of which makes it comparatively expensive as well as—to quote the words of Mr. Cufflin, the Chairman of the Islington (London) Highways Committee—"disagreeable to travelers, agonizing to the horse, and very costly to the owner of the horse."

A source of considerable economy both in the cost of construction of broken stone pavements, and their greater durability by the adoption of the heavy steam-roller, rests in the fact that the metaling of the road can be used of much greater size than if the road were not rolled. Macadam observed that "the size of stone used in a road must be in due proportion to the space occupied by a wheel of ordinary dimensions on a smooth, level surface. This point of contact will be found to be, longitudinally, about an inch, and every piece of stone put into a road which exceeds an inch in any of its dimensions is mischievous." He at length came to "hold six ounces to be the maximum size." But Macadam overlooked the fact that the larger a stone is the stronger it is, and his ignorance of the possibility of binding the material of the roadway by any other means more powerful and rapid than the wheels of vehicles, led him to the conclusion he arrived at. The larger the calibre of the stone that can be made to bind, the better for the durability of the road. The larger the stones are, the fewer are the angles of the stones in a given space, and, consequently, so much less attrition is there; less grinding to dust, less wear and tear. In a well-made and thoroughly compacted broken stone pavement, there is but a very small proportion of open space between the stones, which should be filled, while the road is being constructed or undergoing repairs, with good sharp sand, or some material not liable to crush and grind to powder. With the aid of the steamroller, a macadam road need present nothing but a smooth, hard, clean surface, the only dirt formed on it being from the wear of the stone to a greater or less extent in proportion to the traffic. The roadway is at once made ready for the traffic, instead of being left with sharp, loose stones to injure horses, destroy vehicles, and make traveling a nuisance for months after the road is made.

A steam-roller similar to the one we illustrate rolled down a surface of 2,225 square yards of newly metaled road at Manchester, England, in ten hours, with a consumption of six cwt. of coke, while on another occasion six hundred square yards of similar road was rolled smooth and solid in hours, the consumption of coke being three bushels. The daily cost of working a fifteen-ton steam-roller may be safely estimated at not more than $10, including wages, fuel, wear and tear, etc.

The result of using the steam-roller in India is, according to the reports of the government, that " the cost, of a roller can be saved in 3½ months." The evidence of Mr. Paget, the Engineer of the London Metropolitan Board of Works, is, that when the eleven hundred miles of' macadam road in London are all repaired by the aid of the steam-roller, "a saving to the rate payer will be effected of £140,000 per annum." The testimony of the officials of the parishes in London, who have already adopted steamrolling, is that the roadways last "double the time without repairs;" and the assurances of the value of the heavy steam-roller, wherever it has been used in this country, are equally favorable. The written testimony of Mr. Brennan, of Orange, New-Jersey, and of Mr. Culyer, the Engineer of the Brooklyn Prospect Park, is, that their roadways are now constructed cheaper, and are smoother, more cleanly, more durable, and in every way give better results than before the introduction of steam road-rolling. Mr. Culyer adds, " I do not doubt but that in a few years we shall conclude to make use of the immense store of stone supplied to us.at first hand by nature, and so work up a system of ways which shall be more in accord with the spirit of the age, serve our convenience better, and, in the long run, our pockets too. I do not despond of seeing every town of any note owning its own stonebreaker, and an Aveling & Porter steam road-roller, very much to their own comfort and profit." |

|

1871 Aveling & Porter, Steam Road Roller

1871 Aveling & Porter, Steam Road Roller

1871 Aveling & Porter, Steam Road Roller (Rear View)

1871 Aveling & Porter, Steam Road Roller (Rear View)

|

|