Manufacturers Index - Thomson-Houston Electric Co.

Thomson-Houston Electric Co.

Lynn, MA, U.S.A.

Manufacturer Class:

Steam and Gas Engines

Last Modified: Mar 19 2023 12:04PM by Jeff_Joslin

If you have information to add to this entry, please

contact the Site Historian.

|

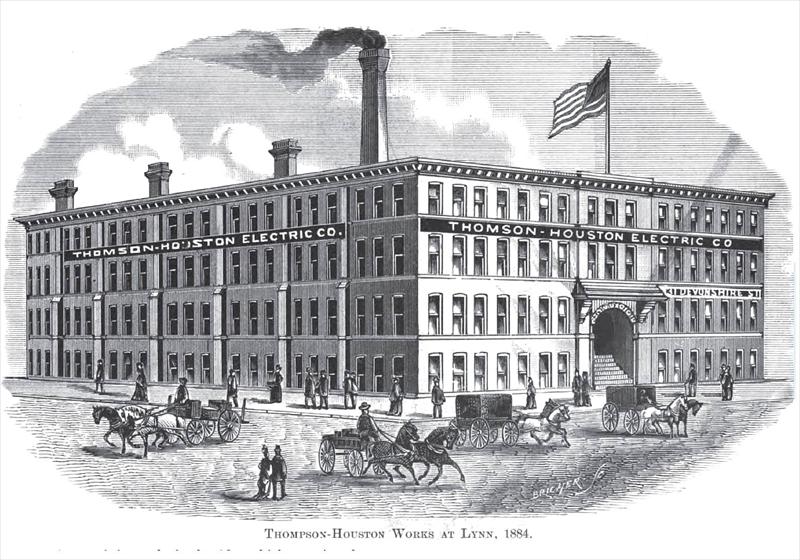

In 1880 the American Electric Co. was established in New Britain, CT, with William Parker as president, Frederick H. Churchill as treasurer and general manager, and researcher and science teacher Elihu Thomson as "Electrician", which was a novel word at the time. Churchill was reportedly the driving force in establishing the business, his primary motivation being attracting businesses to New Britain. Edwin Houston, a colleague and friend of Thomson, was also involved in the establishment of the company. The company set out to develop the generators, transformers, lighting systems, and motors that were needed to electrify both cities and individual manufacturing businesses.

The American Electric Co.'s initial capital was $87,500, which at the time was more than sufficient for most businesses, but it proved inadequate to the ambitions of the founders in a highly competitive and fast-evolving technology, which limited the company's ability to develop, manufacture and sell products. Churchill died in 1881; Thomson and Houston lacked business experience and without Churchill's help they were unable to raise more capital in New Britain.

One early customer was in the town of Lynn, Massachusetts, where the company installed an electrical plant in the armory to supply power to the Coffin & Clough shoe factory among other businesses. Seeing the success of that venture, local newspaper owner Silas A. Barton visited American Electric Co. to discuss a second installation in Lynn, and learned that the company was in financial distress. He returned to Lynn and solicited interest among local businessmen to invest in American Electric. The owner of that shoe factory, Charles A. Coffin, agreed to participate, and soon Barton and Coffin, with the involvement of Thomson and Houston, incorporated the Thomson-Houston Electric Co. in Philadelphia, acquired most of the assets of the American Electric Co., and relocated the business to Lynn, with Charles A. Coffin as president. Houston did not make the move to Lynn and ceased his active involvement in the company, remaining as a professor of physics.

Thomson brought in one of his former students, Edwin Wilbur Rice, Jr., as his assistant; in 1885 Rice became factory superintendent and would be granted numerous patents for his improvements to motors, generators and distribution systems. Meanwhile Charles Coffin was proving to be an exceptionally able administrator and strategic planner. Within seven years Thomson-Houston grew to become the third-largest competitor in the American electrical equipment market, with 4000 employees and $10 million in annual sales. They were out-competing the Edison Electric Co. despite having less capital and fewer employees. For a while, Thomson-Houston maintained an advantage over the Edison company by Thomson-Houston's willingness to accept securities as collateral for orders (mainly from utility companies, many of which were new concerns with no financial history), whereas Edison Electric Co. had a "strict rule" of only accepting cash or short-term notes as collateral. After a few years, however, banks were becoming increasingly reluctant to loan Thomson-Houston money on those securities. Coffin responded to this by establishing the United States Securities Co. to take those customer securities and resell debentures to the public. It turned out that the public was not sufficiently willing to accept that risk and the company was forced to scale back their expansion. The financial risks associated with utility companies was slowing down the electrification of the nation; just as Edison and Thomson-Houston were grappling with this problem, so was their main competition, the Westinghouse Electric Co.

The three companies, Thomson-Houston, Edison and Westinghouse, were battling for supremacy in the lucrative business of building electrical systems, including generating stations, transformer stations, distribution systems, lighting systems, electric rail systems, and electric motors. Edison was a proponent of direct-current systems whereas Westinghouse and Thomson-Houston were proponents of alternating-current systems. By 1890 Edison realized that AC was proving to be the superior technology, and so in 1891 Thomas Edison tried to borrow money from banker J. P. Morgan to acquire Thomson-Houston and their AC patents. Instead, in 1892 Morgan acquired both Edison Electric Co. and Thompson-Houston Co., and merged them under the name General Electric Co. Edison served on the new company's board of directors but did not have any managerial or executive role. Charles A. Coffin was president, Elihu Thomson was consulting engineer, and E. W. Rice, Jr. stayed on as technical director. Rice would soon become vice-president in charge of engineering and manufacturing, and became president of the company in 1913. Thomson-Houston's Lynn operations remained an important part of GE's R&D and manufacturing, but Edison's Schenectady operations became the new GE Co.'s headquarters and gradually superseded the Lynn branch in research, product development, and manufacturing. By 1950 the Lynn factory had been converted to the manufacture of jet engines, with the meter and transformer business moving to Somersworth, NH. In 2005 GE sold the meter business to Aclara and moved the transformer business Florida.

Information Sources

- Modern Mechanism, 1895 page 544

- EMF electrical year book, Volume 1 Jun 1921 page 751

THOMSON, ELIHU An American Inventor and electrical engineer, born at Manchester, England, 1853. In 1858, he came to the United States and was educated in the public schools in Philadelphia. He was professor of chemistry and mechanics in the Central High School there from 1870 to 1880, when he resigned to devote himself to electrical research work. In 1880 he became electrician for the American Electric Co., afterward known as the Thomson-Houston Electric Co. This, after consolidation with the Edison Co. in 1892, became the General Electric Co., the largest electrical manufacturer in the world. Among Dr. Thomson's inventions are the three-coil armature for arc dynamos; the constant-current regulator for arc-lighting dynamos: the process of electric resistance welding of metals; the magnetic blowout for switches and fuses and the motor type of electric meter for direct and alternating currents. Since 1892, when the General Electric Co. established its plant in Lynn, Mass., he has resided there, retaining his connection as consulting electrical engineer. In recognition of his extensive contributions to applied science numerous honors have been bestowed upon him. He was president of the American Institute of Electrical Engineers in 1889-90 and the first recipient of the Edison Medal awarded annually by the A. I. E. E. In 1916 he was awarded the John Fritz medal by the four national engineering societies of the United States.

- Electricity, 27 Jul 1892 pgs 17 - 26.

The first officers of the American Electric Company were: President, William Parker; Treasurer and General Manager, Frederick H. Churchill, Electrician, Elihu Thomson. Among the directors were A. C. Dunham, Henry Stanley, and J. B. Talcott. An incident of the early establishment of the factory in New Britain may be mentioned here. The pattern shop of the company being located at a distant part of the building from the main power, it was driven by a dynamo used as a motor fed from the testing room, and used practically for quite a long period as the only source of power in the pattern shop. It constitutes probably one of the very earliest instances of the actual practical use of electrical transmission, or power distributed by electrical currents. This was during the year 1881 and thereafter, and it may be remarked in this connection that all of the turning, sawing, etc., in connection with the production of the first pattern for the early apparatus of the company as made in New Britain was done by electric power. Furthermore, the motor could be started, stopped and reversed, or its speed varied at will by simple adjustments.

Little was accomplished during the three years of this company's existence. The works were not properly equipped with tools, etc., there being only one plane and a few lathes. Money was scarce and new tools could not be bought. The consequence was that Prof. Thomson was greatly hampered in his work, being compelled in the designing of new machines and devices to produce something that would require almost no machine work in their manufacture. An effort was made to sell out to the United States Company, which would have been successful if the latter had been able to make a satisfactory contract with Prof. Thomson. He insisted that a clause should be inserted requiring the United States Company to push the business properly. This clause was rejected, and the sale was off. In the fall of 1882 a controlling interest was purchased by the Brush Electric Co., of Cleveland, and Prof. Thomson resigned.

In June, 1882, a small plant was established in Lynn, supplying light to a score of customers. The plant attracted the attention of a number of Lynn capitalists, including Messrs. Barton, Pevear, and Coffin, who thought, and rightly, that there was more money in the new enterprise than in the business, in which they had previously been engaged.

The Brush interest was bought out by the Lynn gentlemen, who were quick to see the great value of the patents controlled by the American Company, and the practically unlimited field for their development. Prof. Thomson at once returned to his former position. In 1883 they were granted permission by the legislature of the state to increase the capital stock, change the name, and to remove to Massachusetts. The scene of operations was transferred to Lynn in the latter part of 1883, and the Thomson-Houston Electric Company began its career of remarkable financial success, and scientific achievement. The capital stock was soon increased to $125,000. The company was re-organized throughout, with the following named gentlemen as officers and directors:

H. A. Pevear, Pres.; C. A. Coflin, Vice-Pres. And Treas.; E. I. Garfield, Secy.; S. A. Barton, Gen. Mgr.; Directors, Pevear,C. A. Coffin, S. A. Barton, B. F. Spinney, J. N. Smith.

The push and energy of the new management placed the company at once on a solid footing, and the first year witnessed a large increase in the volume of business. Operations were no longer confined to New England. Local agencies were established in all the principal cities, and in many foreign countries.

It was but a short time until the Thomson-Houston Company had assumed a leading position in the electrical field, and had so far outstripped many of its competitors that the advantages of forming alliances with them became apparent. Since that time seven of the electric manufacturing companies have come under the control of the Thomson-Houston Company. These are the Brush Electric Co., of Cleveland, O; the Schuyler Electric Company, of Middletown, CT.; the Excelsior Electric Company, of New York; the Van Depoele Electric Manufacturing Company, of Chicago, 111; the Indianapolis Jenney Company, of Indianapolis, Ind., and the Bentley-Knight Electric Company, of New York. The manufacturing business of the three latter companies was transferred to Lynn, their former factories being closed....

- 1939 Testimony to U. S. Congress regarding concentration of economic power, pages 3598 to 3602, contains a history of the early history of the predecessors to General Electric Co., as given by GE chairman of the board Owen D. Young. Pages 3600-3601 summarize the history of Thomson-Houston Electric Co. This summary, while second-hand, is especially useful because it does not parrot the same word-for-word history seen in at least 90% of the Thomson-Houston histories we can find, and comes from someone who had ready access to primary source information and professional assistance in crafting this historical summary. Of note also is the financial side of the competition between Thomson-Houston and Edison Co., where Thomson-Houston was equal in gross sales and more profitable than the larger Edison Co., in part because they were willing to accept securities as payment for orders. The more conservatively run Edison Co. strictly refused such arrangements. However, banks began refusing to accept these securities as collateral. In 1890 Charles A. Coffin established the United States Securities Co. to hold utility securities and sell debentures to the public. But the public was likewise reluctant to take on the risk of these securities and Thomson-Houston was forced to insist on better financing terms from its customers; the other major industry competitor was Westinghouse Co., which was in the same position on having to require cash or short credit rather than securities, which slowed the rate of electrification nation-wide. This situation was an important factor in the merger of the Thomson-Houston and Edison companies. In Young's words, "Under such circumstances, what could be more natural than to combine the Edison and Thomson-Houston companies, giving the consolidated concern the business leadership of Charles A. Coffin, the inventive genius of Edison and Thomson, eliminating patent conflicts which were threatening both concerns, and bringing together the financial interests in Boston which had supported Thomson-Houston with the great prestige of Mr. Morgan and his associates in New York?"

- 1949 book, The Life and Times of Andrew Jackson Sloper, 1849-1933.

...He had soon learned from them that in contrast to Thomas A. Edison they had not been getting from Philadelphia people the financial support of which they were badly in need. After receiving assurances from the two professors that they would come to New Britain to live and work if he would promise them financial backing, Mr. Churchill returned to New Britain filled with enthusiastic plans for the future. Before proceeding immediately with his plans, however, Mr. Churchill made a trip to Europe especially to see the electrical displays at a World's Fair then being held in Paris. Going on from Paris to London, Churchill met many distinguished English scientists, among them Lord Kelvin, all of whom were carrying on experiments seeking to develop additional uses for electricity. Soon after returning from Europe more enthusiastic than ever regarding the future of electricity, Fred Churchill conducted an aggressive personal campaign among the prominent well-to-do citizens of New Britain and vicinity seeking to secure subscriptions to enough stock in a new corporation to provide the necessary financial backing for Professors Thomson and Houston so he could bring them to New Britain. As a result of his efforts, a new corporation was formed with inadequate capital of only $87,500. The company adopted the name of American Electric Company and Mr. William Parker, the very impressive-looking and erudite secretary of the Stanley Works, was elected president; Mr. Churchill was elected treasurer and general manager, and Professor Elihu Thomson of Philadelphia was given the title, quite new in the business world, of "electrician."

- 1991 book Innovation as a Social Process: Elihu Thomson and the Rise of General Electric, by W. Bernard Carlson, provides a more detailed view of the operations of the American Electric Co. and the Thomson-Houston Co.

- Wikipedia entry on the Thomson-Houston Electric Co.

- Wikipedia biography of Edwin W. Rice, Jr.

- Wikipedia biography of Elihu Thomson.

- Wikiedia biography of Edwin J. Houston.

- Wikipedia biography of Charles A. Coffin.

- Former GE Meters employee Bob Lee provided us with information on the activities of GE's meter and transformers business after World War II.

|