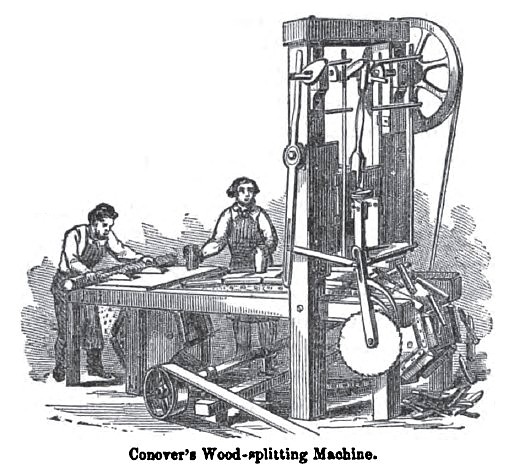

Jacob Conover sold a patented wood-splitting machine in the mid to late 1850s. He aggressively pursued any infringement of his patent, and court records provide some insight into his machine, as detailed below.

From 1855 "Transactions of the American Institute of the City of New York"

Information Sources

- Transactions of the American Institute for the year 1856, including that year's Fair of the American Institute: J. A. Conover, 130 Horatio, street, for a wood splitting machine. Diploma.

- RE: patent 12,857: In the case of Jacob A. Conover v. Peter R. Roach et al., heard before Judge J. Hall of the Southern District of New York in January 1857, Conover alleged that the defendants were infringing this patent. The judge summarized Conover's machine as follows.

The blocks of wood were placed upright on an endless movable bed. A plate with an elastic pad held the block down to the bed during the descent and the rising of the knife. The knife had four blades forming a cross, working through a corresponding slot in the plate. As soon as the knife cut through the block and was again lifted above the block and plate, the plate was raised by the operation of a cam, and a forward motion of the bed took place to advance or feed the next block.

The patent claimed the movable bed in combination with the reciprocating cutters operating at right angles with the surface of the bed, plus the combination of the bed and cutters with the clearing-plate, plus the combination of the reciprocating clearing-plate with elastic pad plus bed and reciprocating cutter such that the clearing-plate both holds the blocks and clears the cutters. The defendants were using a machine that was apparently based on the "Howard patent" (RE359?). The jury found that the defendant's machine did infringe.

In another court case involving this patent, Conover v. John H. Dohrman and John H. Peipho, heard by Judge J. Shipman of the Southern District of New York in March 1868, Conover asked for an injunction against the defendants, who were using a machine of design similar to that covered by this patent. The defendants argued that their machine had a cutter in the same plane as the carriage, whereas the patented machine has the cutter at right angles to the carriage. The judge found that this difference was "colorable and not material, and does not relieve them from the charge of infringement." The injunction was issued as requested.

The inventor sued a kindling-wood dealer, Henry Mers, for infringement, a case heard before Judge J. Blatchford of the Southern District of New York in April 1868. Mers argued that his machine, which was identical to the one used by Dohrman and Peipho, did not infringe, and asked for time to show this. In the meantime, he argued, no provisional injunction should be issued. The judge found that there was a prima faciae case for infringement (because of the previously-mentioned case) and issued the injunction. In a subsequent proceeding, the infringement was affirmed: Mers had used a machine with the patented automatic-feed mechanism and therefore Conover was entitled to all the profits Mers had made from his infringing machine. However, Mers' lawyers argued that Mers had used it only for a limited time and never saw a profit in its operation (Mers sold both split and unsplit wood, and overall his business was unprofitable). The court held that therefore Conover was not entitled to any damages. Conover won on appeal after successfully arguing that Mers was profitable in selling split wood but unprofitable on unsplit wood, and Conover was therefore entitled to the profits on the split wood, an amount of eighty cents per cord. The law was changed in 1870 to allow a patent-holder to recover more than just profits.

In Jacob A. Conover v. John H. Rapp, heard by Judge J. Ingersoll of the Southern District of New York in November 1859. The defendant supposedly had a match-splitting patent but we have been unable to find any such patent; perhaps Rapp was an assignee rather than the inventor. In any case, Rapp's machine used an endless belt to feed the stock but the stock did not actually ride on the belt. The jury had some trouble reaching a verdict but eventually found in favor of the plaintiff. The defendant was unsuccessful in getting a retrial.

In James H. Johnson v. John G. McCullough et al., heard by Judge J. Giles of the District of Maryland in April 1870, the plaintiff had been assigned the patent rights for Maryland, and he sued the defendants for infringement. The judge noted that the plaintiff had been assigned the Maryland rights before the patent expired, and had again been assigned the rights to the extended patent. The judge also said, 'the machine used by the defendants... clearly infringes the Conover patent. Never has there been a clearer case of infringement." The differences—a V-shaped knife rather than a cruciform knife, and the bed was lately used without flanges (although the judge suggested that these were present at the time the infringement bill was first filed), but the differences were immaterial. The defendants produced George Page to testify that he had invented and made a similar machine antedating the Conover patent. The judge said, "Mr. Page's testimony is very confused, as will be found by reference to it; but upon a careful review of the testimony of Page, Sturtevant, and others, I conclude that there was no such machine constructed by Page prior to date of Conover's patent. I have also examined all the testimony relating to the Shaw model, and find that it does not show more than the making of a model, and not of any practical working machine, which is necessary to overthrow a patent. I therefore hold that the complainant is entitled to a perpetual injunction and to an account."