In 1828, William Woodworth, a house carpenter from Hudson, NY, convinced a neighbor to cover part of the cost of patenting a planing machine that Woodworth had designed and built. The neighbor, James Strong, reportedly received a half share of the patent, although this was not formally registered at the time the patent X5,315, was granted.

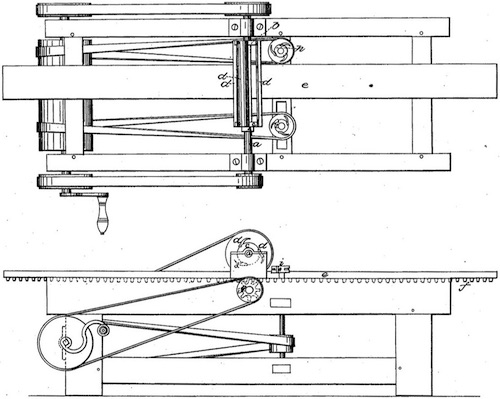

Drawing for Patent X5,315

Woodworth manufactured machines for several years, but did not have the financial resources to take full advantage of his lucrative patent. He sold all but a small portion of his patent rights to a syndicate of three wealthy individuals: Samuel Schenck, John Gibson, and Samuel Pitts (the neighbor, Strong, was bought out at this time, if not before). The syndicate divided up the U.S. into three territories, with Schenck taking New England, Pitts taking the then-Western states, and Gibson taking the in-between states. Within a metropolitan area, the syndicate granted a limited number of planing-mill operators a license to run a Woodworth planer. The operators were required to charge exactly $7 per 1,000 lineal feet, with $3 of that returning as a licensing fee to the syndicate. This arrangement was lucrative both for the syndicate and for the operators.

The machines themselves were manufactured at first by Schenck or Gibson; later on, other manufacturers were licensed to make the machines, including J. A. Fay & Co.; Frink & Prentis; Tredegar Iron Works; and Goodell, Braun & Waters. In 1836 Woodworth applied for and was granted a new patent, 80, which provided some relatively minor improvements to his original design. Woodworth died in 1839, and the patents went to Woodworth's son, William W. Woodworth, plus Jason G. Wilson and Edward Bloomer. In 1842 an extension was obtained for the 1828 patent; the reason for requesting the extension is that the high cost of litigating the patent had consumed much of the profits. Then, in 1845, the syndicate applied for another extension to the patent, including a reissue of the original patent that enlarged the scope of the patent beyond what was claimed or shown in the original. The patent office rejected the extension and reissue application, but the patent owners subsequently bribed members of Congress and obtained them, despite numerous contrary petitions to Congress and the Senate. The reissued patent illicitly expanded the coverage to include what was covered by the expired Uri Emmons patent of 1829.

Patent licensing fees created an enormous cash flow that allowed the patent holders to litigate potential competitors into oblivion. In a couple of cases, a competitor successfully defended himself against patent challenges, but then accepted a large sum from the Woodworth patent holders to sell out; D. Barnum of New York was one, and George W. Beardslee of Buffalo and Albany was another.

An 1852 article in Scientific American claims that the "public are now paying fifteen millions of dollars a year for work done by the Woodworth machines," when other machines could do the work for only $3 million. With the twice-extended patent due to expire in 1856, the syndicate tried to obtain yet another extension, with Gibson alone reportedly spending $250,000. But this time sawmill operators and machinery manufacturers organized a massive protest, orchestrated through the pages of Scientific American, and defeated the syndicate.

Now, how much credit should Mr. Woodworth get for the invention of the modern cylindrical-head planer? Joseph Turner was the machinist who worked with Woodworth to build his first planers, and Turner was witness to the first patent-infringement lawsuit initiated by Woodworth, in 1833 (quoted from Planers, Matchers and Molders in America):

"After the decision of the court, we went to the hotel where Woodworth put up, and told him the decision, and that he must write a new specification, and claim only what he was entitled to; when we told him, he smiled and said the whole of them were fools, for they occupied the time of the court for three days on what he could have told them in five minutes; that he was not the inventor of it; he first saw it among the Shaking Quakers in the western part of the State of New York. I was astonished to hear him say that, after selling the patent."

Information Sources