|

Title: |

1878 Article-Ransomes & Sims, & Head, Portable Straw Burning Steam Engine |

|

Source: |

International Exhibition at Paris, 1878, pgs. 160-162 |

|

Insert Date: |

3/31/2015 3:41:51 PM |

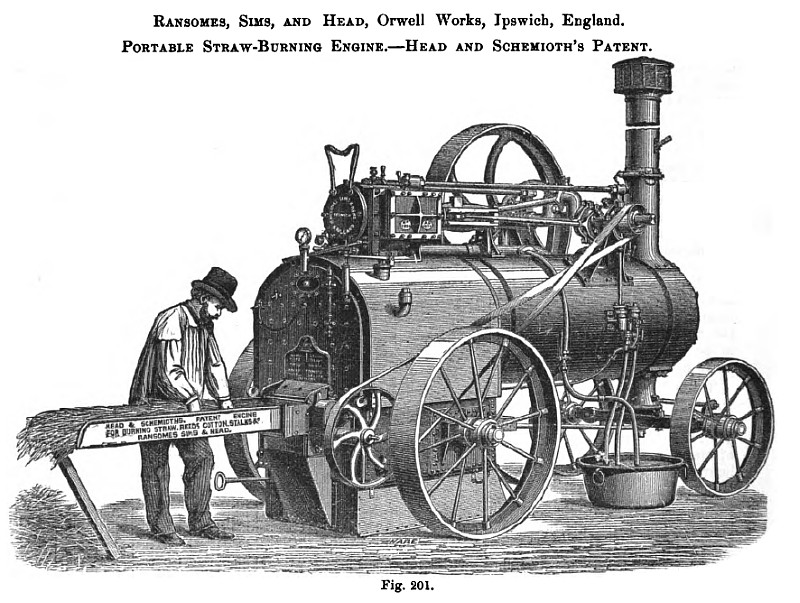

The general construction of these engines is similar to that of the portable engines manufactured by this firm and already described, with the addition of an apparatus fixed to the fire box shell, by means of which straw, reeds, or any kind of vegetable matter can be consumed, or when required the furnace can be adjusted to burn the ordinary fuel, such as coal, wood, peat, &c. The boiler tubes are also somewhat smaller than those usually employed in portable engines, and a further variation is made in increasing the grate area and total heating surface.

The following is extracted from a paper read by Mr. Head, Assoc. Instit. C.E., before the Institution of Civil Engineers in London (vide “ Minutes of Proceedings Instit. C. E.,” vol. xlviii), and gives an exceedingly clear description of the apparatus :—

The theory of the invention is that the fuel should be forced, by a continuous mechanical feed, into the furnace in a thin stream in the form of a fan. The fresh fuel is practically held in suspension for a short time, which allows the separate stalks to become immersed in the flames. The long pieces of straw, reeds, or brushwood have the effect of stirring up the half burnt material in the furnace, and of keeping the whole in motion, besides permitting a free ingress of atmospheric air.

The apparatus designed for feeding the straw, reeds, and other vegetable refuse into the fire box, consists of a pair of serrated rollers, which, in the case of engines of from 6 horse-power to 20 horse-power, are about 5 inches in diameter and 18 inches long, placed at a minimum distance of ¼ inch apart. The upper roller is, however, capable of rising, so that the distance between the rollers can be increased to 1¼ inch, and thus allow for different thicknesses of material. The under roller is set in motion by a strap from the crank shaft of the engine, and makes about 45 revolutions per minute; when the engine is getting up steam this roller is turned by hand with an ordinary crank. The upper roller moves at the same speed, and is connected with the under one by wheels with long teeth. The rollers are set in a cast-iron frame, which is fixed to the boiler by a hinge. To the front of this frame there is attached a trough, for holding the supply of vegetable fuel to be fed into the furnace. Above the rollers there are three flaps, which enable the stoker to look into the fire box, and also to use a poker if necessary.

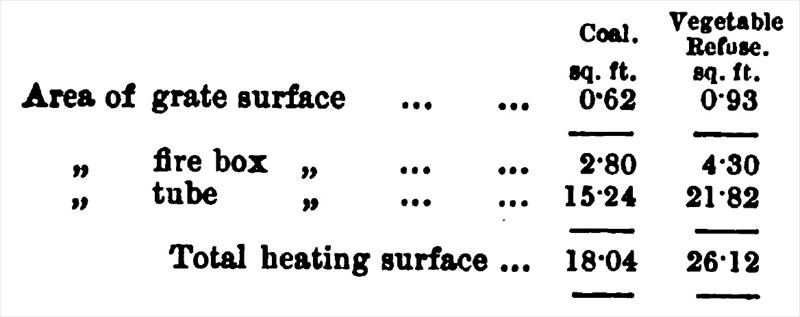

To test the practical value of this apparatus, and to arrive at the best proportions of heating surface and the best position for the automatic feeding apparatus, three engines, each of about 10 nominal horse-power, were constructed by Messrs. Ransomes, Sims, and Head. In two of these the amount of tube and grate surface most suitable for vegetable refuse was determined. The following table shows the comparison between the grate area, the fire box surface, and the tube surface, for coal and for vegetable products respectively, per nominal horse-power:—

(See Table 1)

It is usual to have a deeper fire box when consuming straw and other similar products than is required for coal. The experiments also demonstrated that tubes of 2¼ inches in diameter give a better result in the consumption of vegetable products than tubes of 2¾ or 3 inches in diameter, the size usually employed in portable engine boilers adapted for coal.

After having ascertained the best approximate heating surface for these boilers, two difficulties remained to be overcome. One consisted in finding out the exact point at which to inject the vegetable fuel into the furnace, and the other in preventing the deposit of silica and slag on the grate bars. The first problem was solved by the construction of a third locomotive boiler, with additional heating surface, as specified in the foregoing table. Instead of a fixed hole for feeding the furnace with fuel, a long rectangular aperture was made in front of the boiler, ranging from within a few inches of the crown down to the bottom of the fire box. In front of this aperture the self-acting feeding apparatus was fixed at different levels, the results of the experiments being registered every day. It was found that when the fuel was injected into the fire between 5 and 6 inches from the top of the grate bars, the greatest economy was obtained, there being a more rapid combustion with less smoke than at any other position. At this height the half-burnt and the fresh fuel were kept continually stirred by the fresh fuel coming into the furnace through the rollers. The experiments also clearly demonstrated, that if damp straw is fed on to the top of the fire, as when stoking wood or coal, the fire is almost quenched, and the amount of smoke evolved increases largely; but if the fuel is forced into the hottest part of the fire, and is supplied alternately on the right and the left-band sides of the fire box, so that the fire on one side is always clear and bright, combustion can be maintained with vegetable refuse containing more than the natural amount of moisture.

The deposit of silica on the bars varies according to the nature of the vegetable fuel, the proportion of silica being greater in straw and vegetable matter grown in hot than in cold countries. The silica is not deposited in hard masses on the bars, so as to prevent the proper ingress of atmospheric air, until after the engine has been at work for several hours. It was found that if an apparatus could be made to act before it became glomerated the space between the bars could be kept as free and open as when burning coal or wood. Many experiments were tried with variously shaped grate bars, with self-acting bars like Juckes', and with rotary prickers turned by a handle outside the boiler; but the simple apparatus now in use has proved entirely efficacious. It consists of a rake with five or six teeth, according to the width of the fire box, the top of these teeth projecting about 2 inches above the grate bars. One end of this pricker is attached to a handle, which projects outside the ash pan, and can be worked by the stoker, and the whole apparatus slides backwards and forwards upon two wrought-iron guides underneath the grate bars. When the apparatus is used it is drawn from the back to the front of the fire box along one side of the grate bars. It is then shifted to the other side of the 4-inch space, and travels from the front to the back of the fire box alongside the other side of the space, and thus cuts away all the deposit of silica, which falls into the ash pan.

There was also a slight deposit of silica and slag in some of the tubes, especially in the two lower rows, which impeded a proper generation of steam. To obviate this, and to prevent the necessity for stopping the engine and cleaning the tubes, a steam jet, consisting of a wrought-iron pipe with a brass rose at one end was attached, with an India rubber pipe, to a cock in front of the boiler. When the tubes were furred this apparatus was inserted through the flaps in front of the boiler, and the whole of the silicious deposit was blown through the tubes into the smoke box.

Some difficulty was experienced in dealing with the light ashes, which were deposited in large quantities in the ash pan, when the engine was at work in the steppes of Russia and Hungary, where the strong winds have a tendency to blow the hot ashes out of the ash pan. In order to keep the ashes damp a pipe, connected with the feed pump, was carried from the pump along the front of the Are box. This pipe was pierced with holes at different angles, which ejected water on to all parts of the ash pan. The arrangement was found most effectual, not only for damping the ashes, but also for keeping the fire bars cool. The combustion of the fire in these boilers is so perfect that but few sparks escape from the chimney. Although in some cases the funnel-shaped American spark catchers have been fixed to the engines, yet the ordinary spark catcher used for wood has proved amply sufficient for all practical purposes. It has also been found in practice that the sparks occasionally emitted from straw-burning engines are not so dangerous, or so likely to ignite anything upon which they may fall as the sparks from the chimneys of wood-burning engines.

In those cases where it may be necessary to burn coal, wood, peat, or sawdust in the boilers which have been described, the mechanical feeding apparatus is removed, and in its place an ordinary fire door is substituted. Instead of only four or five grate bars, placed at intervals of about 4 inches apart, the full number of grate bars is inserted in the fire box, with spaces of about 1 inch to f inch between the bars. The sliding pricker is also removed.

Steam engines were constructed for burning peat, sawdust, &c, before straw was used as fuel under steam boilers; but the proportion of carbon being smaller, and that of water larger, in peat than in coal, it became necessary to increase the grate area and heating surface, in order to compensate for the difference of calorific effect between equal weights of peat and coal. When sawdust, mixed with a small proportion of slack coal, or with chips of wood, is burned under the boiler—which often happens with engines used for driving sawmills or woodworking machinery —an amount of grate surface equal to nearly 1 square foot per nominal horse-power is required, so as to obtain a thin fire spread over a large area.

As the proportion of heating surface necessary for burning vegetable refuse is about the same as that required for peat, sawdust, &c, it follows that the improved boilers can be employed in a modified form for burning other substances, although their chief adaptation is for the combustion of straw, reeds, brushwood, cotton stalks, and megass. Should these boilers be used for coal a similar change is introduced in the general arrangement of the fire box as for peat, but the proportion of grate surface to the amount of water required to be evaporated being much too large for the economical consumption of coal, it is usually diminished by inserting a row of fire-bricks at the back and front of the grate bars, so as to reduce the area of the grate to 0.7 square foot per nominal horsepower.

Many experiments have been made with these engines to arrive at data respecting the consumption of straw; but it is almost impossible to give such accurate figures as those tabulated for coal, owing to the variety in the straw grown in different countries and soils—some producing results below those already specified, and others exceeding them. It is well known that straw imbibes moisture rapidly, and the state of the weather has much to do with the quantity of vegetable fuel consumed by an ordinary tubular boiler.

With a single-cylinder portable engine of 10 horsepower, the diameter of the cylinder being 10 inches, with a length of stroke of 13 inches, the pressure of the steam being 76 lbs., cut-off at about ½, and the revolutions being 140 per minute, the straw consumed was 4½ cwt. in one hour and ten minutes, the load on the brake being 22.59 horse-power. The consumption of straw per horse-power per hour was 19.11 lbs., which, taking 6 lbs. as the average consumption by this engine of coal per horse-power per hour, gives the proportion of the consumption of coal to straw as 1 to 318.

With a single-cylinder portable engine of 8 horsepower, the diameter of the cylinder being 9f inches, with a length of stroke of 12 inches, the pressure of the steam being 78 lbs., cut-off at between 1/3 and ½, and the revolutions being 140 per minute, the straw consumed was 7 cwt. in two hours and twenty minutes, the load on the brake being 16.06 horse-power. The consumption of straw per horse-power per hour was 20-92 lbs., which, taking 6 lbs. as the average consumption by this engine of coal per horsepower per hour, gives the proportion of the consumption of coal to straw as 1 to 3.18. The fire box of this engine was fitted with a baffle plate, fixed in front of the tubes in such a manner that the flame and half-consumed straw did not impinge directly on the tube plate.

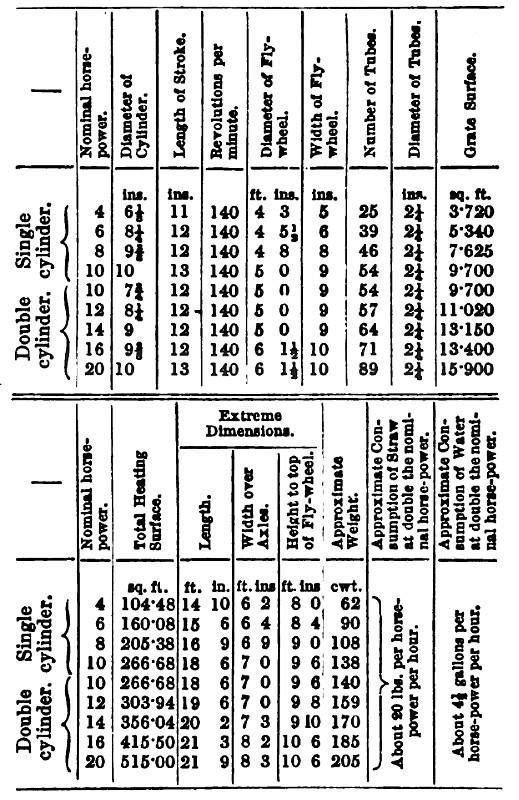

The accompanying table shows the proportions, &c, of the engines and boilers built upon this system:—

(See Table 2)

General dimensions, weights, and measurements of portable engines fitted with Head and Schemioth's apparatus for burning straw and other vegetable refuse, supplied with single slide valve, single feed pump, and branch pipe from exhaust for heating feed-water.

The straw-burning apparatus can be applied to ?xed boilers of all kinds, and it has likewise

been ?tted to several of the ploughing engines

manufactured by John Fowler and Co. with considerable success, enabling steam to be employed for ploughing on various estates in Russia, where there was no other fuel available

but straw and brushwood. The average consumption of straw per acre ploughed by the two engines when ploughing 10 inches deep was 6 cwt.

Prices.—Single cylinders: 4 horse-power £150; 8 horse-power £210; 12 horse-power £28. Double-cylinders: 8 horse-power £235; 16 horse-power £375; 20 horse-power £450; 30 horse-power £640.

Manufactured by Messrs. Ransomes, Sims, and Head. |

|

1878 Ransomes & Sims, & Head, Portable Straw Burning Steam Engine

1878 Ransomes & Sims, & Head, Portable Straw Burning Steam Engine

1878 Ransomes & Sims, & Head, Portable Straw Burning Steam Engine (Table 1)

1878 Ransomes & Sims, & Head, Portable Straw Burning Steam Engine (Table 1)

1878 Ransomes & Sims, & Head, Portable Straw Burning Steam Engine (Table 2)

1878 Ransomes & Sims, & Head, Portable Straw Burning Steam Engine (Table 2)

|

|