|

Title: |

1884 Image-Southwark Foundry, Porter-Allen High Speed Steam Engine |

|

Source: |

The Engineer's Handy Book 1884 pg 331 |

|

Insert Date: |

3/29/2011 11:03:07 AM |

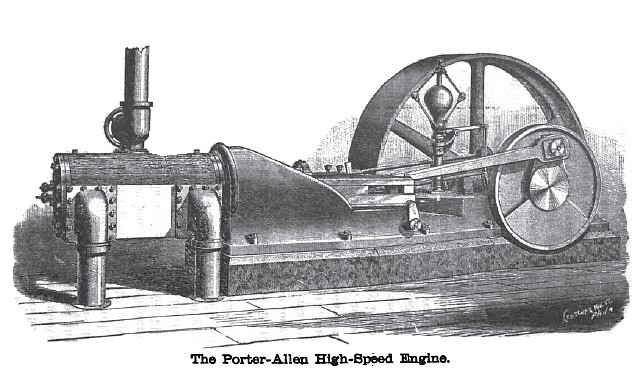

The Porter-Allen High-Speed Engine.

The cut on page 331 represents a front view of the Porter-Allen High-Speed Engine. As will be observed, the bed-plate is of the box form, the surface of which is raised near the centre line. The main-bearing being brought as near as possible to the centre line of the cylinder, the breadth and depth being of sufficient proportion to resist all strains, it presents no sharp angles that would be a source of weakness. In fact, the bed-plate was designed to secure absolute rigidity under high-piston velocity, and correspondingly high steam-pressures, as well as a support for the cylinder, thus making a self-contained horizontal engine. The cylinder is overhung from the front end of the bed-plate, without any support excepting that which is derived from the butt-joint which it forms with the housing, which admits of equal expansion on all sides, and prevents the possibility of getting out of line. The rigidity of these engines may be judged from the fact that not the slightest vibration is experienced under the highest piston-velocities and steam-pressures; nevertheless, when of necessity they have long stroke, there is a temporary support placed under the cylinder.

The steam- and exhaust-chests are located on opposite sides of the cylinder, and cast in one piece with it; and the valves and seats are so arranged, that the removal of a small bonnet gives easy access to them. At the back of the steam-valves, an adjust able pressure-plate is introduced; this plate is made of a form which is calculated to resist the steam-pressure without deflection, and which is held against two inclined supports above and below the valve by a bolt screwed through the bottom of the chest. If this bolt is backed sufficiently, the steam will cause the pressure-plate to seize the valve. By turning the bolt forward, the pressure-plate is raised, and also moved away from the valve. The engineer can test each valve for leakage, by unhooking the disengaging hook, with which all these engines are provided, and work the valves by hand under steam-pressure by the starting-bar, while the assistant adjusts the bolt on the pressure-plate. If there has been no wear, the slightest movement of the bolt will cause the valves to be seized; but if there is any wear, it can be adjusted in a few moments.

The exhaust-valves work under the pressure in the cylinder, and have short movements, each valve opening four passages for the release of the steam. The exhaust-valve seats are formed on the covers of the chambers in which they work, and on which, also, the outlets are cast. They drain the bottom of the cylinder; they are very conveniently arranged for facing, adjustment, or repairs, and, by removing small bonnets, they may be taken out and replaced without any inconvenience. The release of the steam is one of the most remarkable features of these engines, as the link gives to the valve an admirable movement in every respect. The movement of the exhaust-valves being most rapid at the instant of release, the steam can be held to almost the end of the stroke, in consequence of the port opening to its full width at the instant the crank reaches the centre.

The eccentric is forged on the shaft, which gives compactness, exactness of construction, and prevents it being shifted by accident or design. The cylinder-heads are designed to receive the steam from the boiler, by which arrangement the clearance is reduced to a minimum, and the economy of the engine increased. Great pains are taken with the crank- and cross-head pins, which are made of the best steel, and hardened. The connecting-rod boxes are made of gun-metal or bronze. The upper and lower sides of the cross-head wrist are made flat. The crank-pins are of unusual diameter in proportion to their length, which brings the flattened connecting-rods close up to the faces of the accurately balanced disc-cranks. The construction of the marine pillow-block bearings is the result of much study, and presents many improvements over those to be seen in ordinary engines. The flywheels of these engines, like the cranks, are turned and accurately balanced, which insures smooth motion in the revolving and reciprocating mechanism. The regulator employed on these engines is what is known as the Porter governor, and is peculiarly adapted to this class of engines; and, in consequence of being more powerful and sensitive than any other governor in the country, it has been successfully applied to the controlling of the valves of other engines which no other governor in the market would regulate.

The high-speed engine has not been heretofore appreciated in this country. As has been heretofore stated in this book, most intelligent American engineers entertain the idea that there is nothing to be gained by running an engine at such high velocity, or employing extraordinary high pressure, because an engine, to run at such an extraordinary speed, needs to be built with great care, of first-class and expensive material, which increases its first cost. Besides, the cost of maintenance of such a machine is a continual source of annoyance. It is a well-established fact in mechanism, that haste, beyond a certain limit, induces waste, and that any attempt to force any machine, steam-engines and boilers included, induces rapid wear, deterioration, and eventually the destruction of the machine. The high-speed engine is one of the innovations that at different times, in the opinion of their advocates, were going to revolutionize the whole system of steam engineering. But their impracticability soon became evident, and they died out, only to give place to another set of schemes that have proved equally delusive. |

|

1884 Southwark Foundry, Porter-Allen High Speed Steam Engine

1884 Southwark Foundry, Porter-Allen High Speed Steam Engine

|

|