|

Title: |

1871 Article-A. S. & J. Gear & Co., Moulding, Carving & Dovetailing Machines |

|

Source: |

Manufacturer & Builder, V3, Jan 1871, pgs.5-6 |

|

Insert Date: |

2/19/2017 8:33:53 PM |

Dovetailing and Variety Moulding Machines.

Some of the most surprising operations are effected by the simplest methods. The simplest method is not necessarily the most obvious or the most usual. On the contrary, it is quite likely to be the last thought of. For example, to bore a square hole with a round bit is an operation which most persons who have never witnessed would confidently pronounce impossible, a contradiction in terms. Yet it is just as simple a thing as to bore a round hole. As it will tend to make our subject clear, wo will first show how this is done. Mechanics, of course, do not need the information. But future mechanics, and general readers, whose active minds can never be

"Contented merely to enjoy

The things that others understand,"

will be more interested in this unfolding of one of the mysteries of the arts than of those of a romance. At the same time, before we are through, we shall interest our practical wood-working readers by introducing to them a machine which is found as yet in comparatively few shops, yet which is second only to the lathe in range and variety of powers and universal utility, while its moderate cost renders it equally available with the lathe for very moderate establishments.

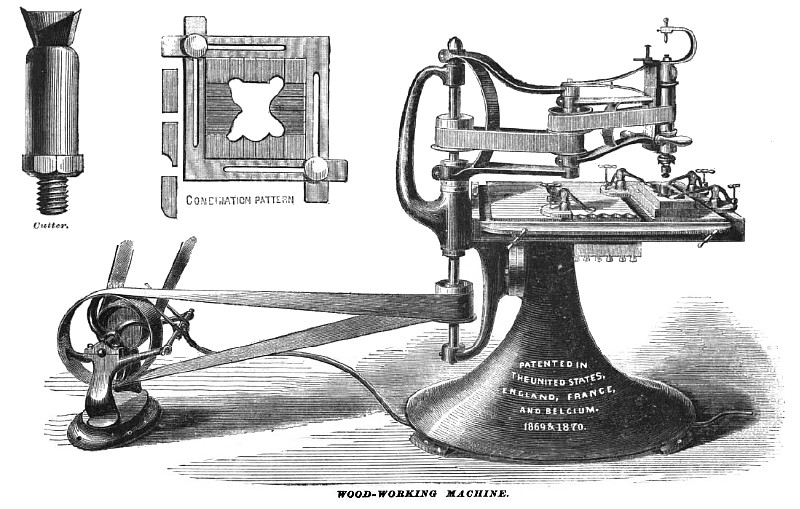

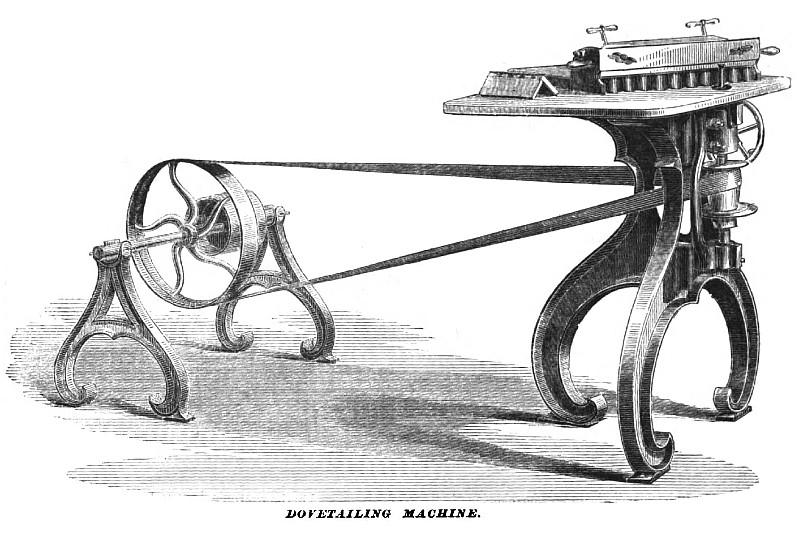

To bore a quadrangular hole with a round bit. We will illustrate this problem by the subjoined cut of a dovetailing bit. The cutter at top will be recognized by its knife edges, set obliquely on opposite sides and in opposite directions, and running up each to a sharp angle. The reader will please conceive the blades as curving spirally around the imaginary axis of the bit, and leaving the inside space hollow, for clearance of chips. Now, the cutting, of course, is done in circular lines, by revolving the bit on its axis; but the result depends on the direction in which the wood is made to approach. If the wood be pushed against the end of the revolving bit in a direction parallel to its axis, so as to make it enter the wood endwise, like an ordinary bit, a round hole results. But by pushing the wood against the blades in a direction at right angles to the bit, (not allowing the wood to extend below the end of the blades and be stopped by the shank,) it is evident that the instrument will enter the wood sidewise, cutting a path for itself, of the same shape, in cross-section, as the outline of its own longitudinal section, whatever that may be. If the longitudinal section of the bit be square—that is , if the cutting edges be parallel to its axis and each other—the path or trough cut will be square, (exactly fitted to bed a square bar of the same size,) and as long as you choose to run it. If round, you would bore a tube, open on one side. If the blades were inclined toward each other, so as to meet at the axis of motion, the result would be a V-shaped trough, or triangular hole. If the blades diverge from each other, or flare, as in the cut, they make a dovetail trough, or quadrangular passage, of which one pair of opposite sides are parallel but unequal, and the other pair are equal but not parallel. All this, supposing the wood to be thicker than the length of the blades, and with leave of the chips. It is evident that a trough or passage of any imaginable shape in cross-section, and following any imaginable series or labyrinth of curves, may be cut in this way, by giving the bit the requisite shape beforehand. To make a perfect bore in this way, however, with its walls entire, round, square, triangular, polygonal, or with sides curved, convex, or concave, it would be necessary to bore a round hole beforehand, in the ordinary way, and then to use a bit with its shank or journal wholly inside its blades, and mounted at right angles on a hollow arm, through which motion would be communicated to the bit by gearing or a wire belt. The necessity for making a hole beforehand results from the necessity of leaving an annular slot through the blades to clear the carrying-arms as they revolve. We are not aware that any actual realization of this method has ever been made, or that it would be of any great practical consequence. But for dovetailing, which makes the only strong corner joint for woodwork, and which would be used, probably, a hundred-fold what it is if the simple machine herewith illustrated were in as common use as it might be, the bit we have described is a perfect implement. The mortises being out at exactly proper intervals, leave tenons of the fit size intermediate. In drawer-fronts, etc., the bit channels out the dovetail on the inside, as at first suggested, leaving the face fair.

A few years ago, all mouldings, unless carved expensively by hand or slowly and skillfully turned in a lathe, were wrought exclusively in parallel straight lines, by moulding planes made to various patterns. A full assortment of these planes formed a bulky and expensive part of an old-fashioned good outfit for a carpenter. More lately, with the horizontal planing-machine cutter, came in the horizontal moulding-machine cutter, plowing the moulding out by a motion in the same direction with a revolving cutter, as the hand moulding plane, and, like it, limited to straight-line patterns. We well remember, and probably many of our readers noticed it, when wavy mouldings first became suddenly common in cheap work which could not have been wrought by hand, and gave us no little perplexity to imagine how they could have been produced by machinery. The next cut and description will reduce this mystery also to a very simple matter.

It will be observed that the horizontal arm or frame, projecting over the table, and carrying pulleys and belts to communicate motion to the bit at the end, has both an elbow and a shoulder-joint, on each of which it moves freely in all horizontal directions without interfering with the constant and rapid rotation of the bit. Therefore, the revolving bit is easily guided to any possible pattern that may be traced on the wood to be cut, or that may be cut in a pattern block, such as is seen clamped on the top of the wood to be cut, to serve for a mechanical guide to the travel of the bit. The mandrel in which the bit is fixed is raised and lowered, and fixed at exact distances from the table at pleasure; or, if left free, the motion is absolutely universal, in every possible direction; and patterns being prepared for guiding the tool to variable vertical movements, all sorts of figures, to which a shape of the tool and pattern-block may be adapted, will be cut with mechanical exactness.

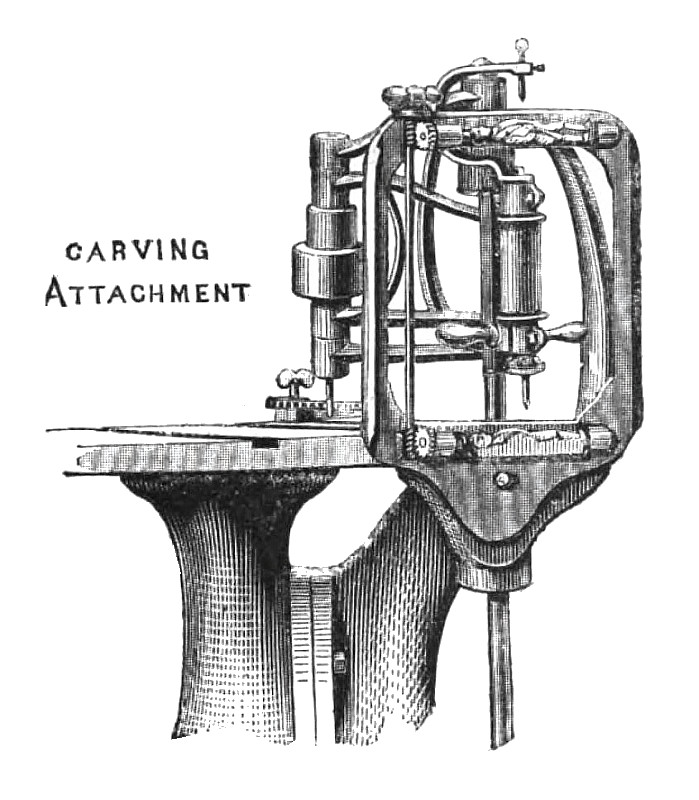

To illustrate, let us first suppose a simple operation with a knife-edge on each side of the bits shaped like a moulding-plane iron. If the surface of wood to be shaped into a moulding be applied to these revolving edges, and the bit be made to travel on a straight line, an ordinary plain moulding will be produced, the same as if done in the old-fashioned way. If, instead of this, a ring of wood or metal be clamped on the top of the flat piece of wood to be cut, in such a manner as to present a guiding outline against the shank of the bit, then the instrument, being made to follow this ring, will cut a circular moulding. After moulding around the inside of the ring, run it around the outside, and a double-moulded circular frame will come out clear, the exterior and interior waste dropping off. It is evident that any other shape, a wavy or serpentine moulding, for instance, may be cut with equal ease and accuracy. Also, that by applying a pattern guide to the vertical movability of the tool, the moulding may be cut with the same rapidity and certainty in vertical waves or other figures. A panel may be cut in solid lumber, for the front of a drawer, for example, with any kind of fancy moulding around its sides, and with other ornaments, ad libittum. In short, there is hardly anything to be desired or imagined, in the shaping of wood, which is not in the power of this versatile invention. The next cut shows the carving attachment, which contains the conveniences for vertical guidance of the tool, and the last shows the mode of forming a great variety of patterns with combination blocks.

Simple as are the principles of this wonder-working machine, it is not to be supposed that the successful execution of the details of its construction has been, therefore, an easy matter. The perfection of simplicity is often the perfection of difficulty and the consummate triumph of genius and perseverance. We are told that the mere adaptation of a fan to blow away the chips from the work as it proceeds, has cost much time and ingenuity, and that upon the success of this simple expedient the success of the machine has, in a great measure, depended. A. & S. Gear & Co., No. 56 Sudbury Street, Boston, are the manufacturers.

US Patent: 97,188

http://www.datamp.org/patents/displayPatent.php?id=2648 |

|

1871 A. S. & J. Gear & Co., Moulding Machine

1871 A. S. & J. Gear & Co., Moulding Machine

1871 A. S. & J. Gear & Co., Carving Attachment

1871 A. S. & J. Gear & Co., Carving Attachment

1871 A. S. & J. Gear & Co., Dovetailing Machine

1871 A. S. & J. Gear & Co., Dovetailing Machine

|

|